A SEED IN THE POCKET OF THEIR BLOOD

A coffee-table book that combines poetry and photography into one artistic unitA Seed in the Pocket of Their Blood (Amphitheatre Publications, 1997; acquired by Syracuse University Press in 2000) is a coffee-table book that combines poetry and photography into one artistic unit as it explores issues of Jewish identity. The book features my poetry linked to the works of many fine artists including legendary Time Magazine photographer David Rubinger; Jim Hollander, the former Chief Photographer for Reuters in the Middle East; renowned Montreal photographer Serge Clément; and acclaimed Toronto portrait photographer Ruth Kaplan.

A Seed in the Pocket of Their Blood is the companion book to the exhibit of the same name that has been viewed widely throughout Canada, with showings in the United States and Israel (see The Exhibit). This project examines the themes of: Jewish life in Europe, the Holocaust, Jewish immigration to North America and love and war in the land of Israel. The book features additional poem/photograph combinations that were not featured in the exhibit.

The book, A Seed in the Pocket of Their Blood, was launched in the United States with a reading at the Canadian Consulate in New York City.

The Participating Photographers

Karolina Barski

Werner Braun

Serge Clément

Linda Dawn Hammond

Eran Harduf

Jim Hollander

Doron Horowitz

Gaye Jackson

Ruth Kaplan

Shimon Lev

David Rubinger

Natalie Schonfeld

The Curatorial Process— Matching Poems to Photographs

The sole criteria for matching a photograph to a poem was that the photograph gives the poem an added dimension or meaning it could not have achieved alone, and vice versa. The result is that one new piece of art is created from the two art forms.

The curatorial process was long and arduous. I searched archives in Canada and Israel, I met with photographers and their representatives and attended numerous exhibitions. It took over a year and a half to curate the book and exhibit (see The Exhibit). I didn’t know what I was looking for until I found it. However as soon as I set my eyes on the ideal image I said, ‘This is it’. The best example is Serge Clément’s photograph of a hand reaching heavenward in the exhibit piece, “The Conflict”. I had an anti-war poem that I knew would turn that photograph into something completely different than what Serge had originally intended when he shot it, while at the same time strengthening my poem with a powerful and unexpected visual.

Photo: Serge Clément

Both Sides

on both sides the lines are long

years you cannot see

a continuous march on the land

all in mourning

carrying their unborn

the amputated families and lovers

the memory haemorrhaging on the deeds

the will of the dead

and this is the torture

to know you have survived

to live it again

in memory, in dreams, in deeds

a prisoner of war

I began with a stack of poems, uncertain of what images I would find and what poems would be included in the exhibit. There were some poems I felt would be easily matched to photographs and in the end I was proven wrong and they were left out of the exhibit.

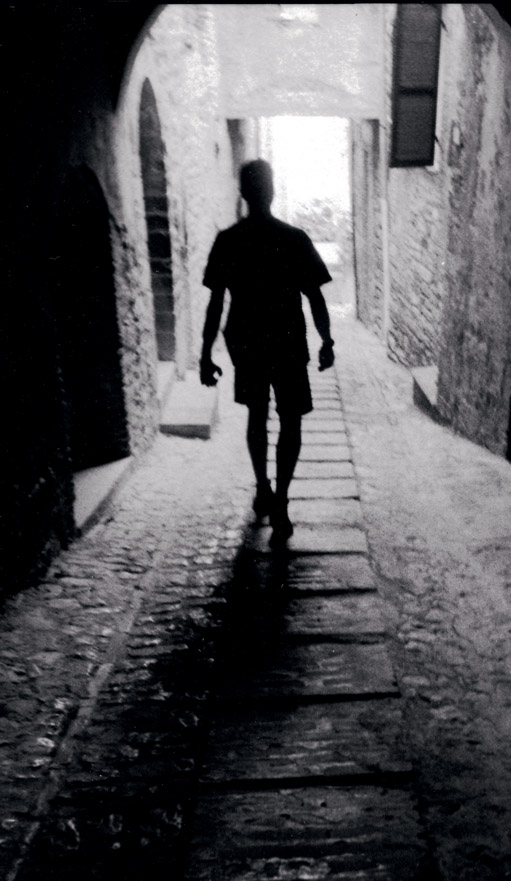

There were others I thought would be problematic in terms of finding photographs for and sometimes I was pleasantly surprised. The one that comes to mind immediately is Natalie Schonfeld’s photograph for “The Sound Traveller”. In the poem I’m going back in time through sounds and the more you know about your past and your ancestry, the more you learn about yourself. The image of the man walking from darkness to light on an ancient street was ideal.

Photo: Natalie Schonfeld

The Sound Traveller

under the full moon I rattle the sacred

artifacts that have passed from hand to hand

calling the voices wherever they are lodging in their lofty retreats

with a clear view of the world to join me in my silence

i give thanks to the fertility of those who carried me in the unfamiliar

sounds of rapids rushing blood the falls where tributaries married

and families merged so I could be born so I would sing this silent song

my tongue stumbles over mountains and plains

sliding backwards over consonants I hear the trapped

echo clawing its way out of Eastern European languages

the journey is of sounds, I move my feet

to the accordion, to this hill where they gathered

as a family three times a year

i evoke the names, slap the straight razor across the leather strap

so the bearded voices appear in my zeyda’s shop

for their Sunday shave, I tap a tea cup with a spoon

its rose pattern, a family crest, brings the din of dinners to the table

i hear the drum roll

of knife and fork on empty plates

the door from the dinning room swinging open

in a house I never knew

my great-grandmother marches in

one hot dish after another and faraway

the creaking of a rocking chair

an unknown voice speaking

of those who lived long ago

i wander in the current of years that runs through my ears

sink in sounds of crusted snow as I come to winter

and wood cottages they called homes

so that my bones would curl into my flesh and I would be them

as they rose in the morning with their foggy breath

as they carried water over the ice to wash

i seek the last ember of the fire that hides under the dead

a seed in the pocket of their blood

A few images fell into my hands but most did not. David Rubinger had a photograph of the blood stained copy of the Song of Peace that was in Prime Minister Rabin’s breast pocket when he was assassinated. There couldn’t be a more fitting image to describe this horrific event and its aftershocks. The peace process had been killed. If you look carefully at the black background you can see what appear to be tiny black bubbles—a texture one would find in leather. David took the photograph in Prime Minister Rabin’s office, using the Prime Minister’s chair as a backdrop.

Photo: Jim Hollander

Jim Hollander’s excellence in photography spans more than one genre, as exemplified by the photos in his book, Run to the Sun– Pampalona’s Fiesta de San Fermin (Master Arts Press LLC, 2002). Jim took the photograph for “In this Amphitheatre”, with a pinhole camera he made specifically for this shot. The results are an incredible image that blurs the lines between a pastel painting and a photograph.

When I first encountered Ruth Kaplan’s work she was photographing people in bathhouses in Europe for a project she had been engaged in for many years. Her work was compelling. I needed someone to shoot a portrait of my grandfather and all her subjects were nude. It was only when another photographer told me that she also photographed people fully clothed that I approached her. Ruth was gracious enough to drive with me to Ottawa to photograph my late grandfather Benjamin Feinstein. Interestingly enough with all the equipment that we took to Ottawa, lighting and lenses, the definitive shot of my grandfather came from a handheld camera, during a break from shooting. My grandfather lived to be one hundred and three. I always joke that he was much younger when that photograph was taken, he was only ninety-seven. Ruth Kaplan is still my favourite portrait photographer in the country, and on top of that she’s a wonderful person.

Photo: Ruth Kaplan

My Grandfather and the Blues

as the cantor holds the last high note

the performance is over

the people smile

and my grandfather

leans over to tell me

“pray putting your soul

into words not some sweet melody”

i think about his life

a village in Russia

where a member of the congregation chanted

the holy texts

shouting leaping crying

by the river that divides

this world from the next

and later at B’nai Jacob

where the cantor stood before all

his head leaning back

while his hands spoke to the L-rd

i turn away unconvinced, then i think

of the blues

how a song is (never sung

but) stomped, broken, shattered as tiny pieces

pierce the vocal chords, how notes and words are dragged

through country back roads and there is only dust

in the throat or the severing of a chord

as a spear strikes the heart

and how sometimes it is my grandfather in synagogue

rocking back and forth

on the edge of a cliff

calling out to the world with everything he’s got

except his voice

Serge Clément is a master of his craft. I love how he orchestrates light and reflection, in a manner that’s so unexpected and totally his own. I remember a photographer coming up to me at one of the openings and saying how he had spent a full day in the Budapest cemetery and still couldn’t get enough light to take photographs and he just marvelled at the way Serge had done it. There’s an element of mystery in so many of Serge’s photos which fit perfectly with what I was doing.

One of the most fascinating things for the landscape photographers was how their work was used to document the human condition, something that generally doesn’t happen with their photographs. Doron Horowitz’s shot of children diving off the ancient walls of Akko ventured into the political realm when paired with the poem, “When You Speak”.

This was true for Shimon Lev and his photograph, “After the Death of Canadian Marnie Kimelman by Terrorists on a Tel Aviv Beach, July 1990”. His photo of a deserted beach was haunting, and the empty chair filled with symbolism.

The best thing that came out of this project was my friendship with Linda Kimelman. Linda is the mother of the late Marnie Kimelman, who was 18 years old when she was killed by a terrorist while visiting Israel. I was living in Tel Aviv at the time and deeply moved by this senseless loss of life and wrote the poem. The Kimelmans live in Toronto and A Seed in the Pocket of Their Blood was set to be launched there. Out of consideration to the family I sent the Kimelmans a copy of the poem and let them know I was prepared to pull that piece from the exhibit for that stop of the tour. It took the family some time to get back to me. I met with Linda and not only did they approve of the poem, they asked for a copy, which I had framed for them. Linda and I struck up a wonderful friendship. I promised them that I would read that poem at every stop on the tour and I kept my word.

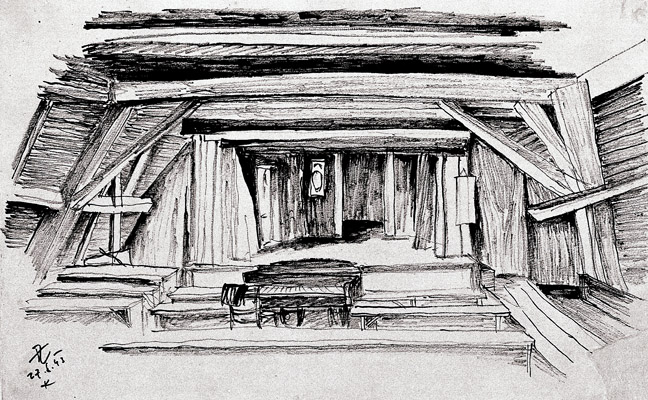

Sketch: Frantisek Zelenka, Ghetto Fighters House Museum

The only piece in the exhibit that does not contain a photograph is “Dora Barack at 95”. Instead there is a sketch of a stage, by Frantisek Zelenka, used for the dramatic productions that were held in a squalid attic in Theresienstadt. I located this treasure at the Ghetto Fighters Resistance Museum (Beit Lohamai Hagetaot). It fit perfectly with the theme of my poem. I met Dora Barack many years ago when I was reading in Los Angeles and marvelled how she kept the Yiddish language alive by creating in it. Frantisek Zelenka was a famous stage designer who was born in Kutna Hora, Czechoslovakia. For two years in Theresienstadt he designed stages and costumes for plays. In 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz where he perished.